There are two subjects that most people probably know very little about: Mennonites and the country of Bolivia. Nevertheless, as discussed in a recent BBC report, over the last 10 years Mennonites living in Bolivia have been involved in an extremely serious scandal in which the use of psychotropic drugs played an essential part. These bizarre events took place in the small Mennonite village of Manitoba (population approximately 1,800) buried deep in the South Western Bolivian countryside.

First some background. What are Mennonites and how did they end up living in Bolivia? Mennonites are a religious group of what are known as “anabaptists”, Hutterites and Amish are other examples. Anabaptists are individuals who believe that baptism is only appropriate when carried out by adults who understand how it affects their relationship with Jesus Christ. These groups arose in Germany during the early 16th century as the Protestant Reformation was developing and evolving its different modes of expression. Anabaptists were always considered to be a radical element of the Reformation and they were frequently persecuted for their beliefs. In order to be able to practice their religion freely, many anabaptist groups were forced to leave their original homeland and migrate to other parts of the world in search of religious tolerance.

The Mennonites were founded by a priest named Menno Simons around 1520. Simons not only encouraged adult baptism but also pacifism and living as simple a life as possible. Because of religious persecution in Western Europe, the Mennonites migrated from Northern Germany to Russia where land was plentiful and they could live an undisturbed existence. Around 1870 however, persecution of different minority religious groups became widespread in Russia and so the Mennonites moved on to Canada, another country with abundant natural resources which welcomed pioneering settlers. Following their move to Canada, different factions began to arise within the Mennonite community. Some became assimilated into Canadian society adopting a contemporary lifestyle whereas others, known as the “Old Colonists”, decided to cling to their traditional way of life. As their forefathers had done, the “Old Colonists” felt a need to move on and left Canada in the 1920s, traveling to South America. Original areas of Mennonite settlement in South America included Paraguay and Mexico, but ultimately many also moved to Bolivia and Belize, two countries that were relatively “out of the way” with plenty of space where they could live in peace. At the present time there are over 50,000 Mennonites living in Bolivia scattered over more than 50 settlements. The Mennonite settlement of Manitoba was founded in 1993. The residents of Manitoba live a radically simple life, far removed from typical 21st century existence. There are no cars, cell phones or other modern forms of technology. “Entertainments” like music and shows are discouraged. Although they live in the middle of South America, the residents of Manitoba do not speak Spanish. They speak Plattdeutsch, a low German dialect related to Dutch and Friesian (think Thomas Mann’s Buddenbrooks). Mennonites work very hard on their farms and have become important elements of the Bolivian farming community, particularly in the area of dairy produce.

Because of their highly traditional lifestyle, men and women have strictly defined social roles. Women wear conservative clothes and are basically “homemakers”. Relationships between men and women are highly regulated. Over the years there has been very little crime in Mennonite communities and, as far as the Bolivian government was concerned, Mennonites were about as law-abiding as people could be. The government basically left them alone to look after themselves—which was exactly what they wanted.

But then something strange happened. Around June 2009, reports began to circulate in Manitoba concerning nighttime attacks on young women. These incidents were all similar. Girls in their early teens would wake up with pounding headaches. They would find their bedclothes soiled with blood and semen and they would feel sore between their legs. In other words, they had been raped but appeared to have no memory of the events or who the perpetrators might be. Other members of their families would also wake up feeling hung over and nobody seemed to know how the events of the previous night had transpired. The frequency of the attacks began to increase to epidemic levels totaling over a hundred victims. Don’t forget that because the Mennonites do not use electricity, there is no street lighting and at night it is really pitch black, making it difficult to see anybody moving around outside. Moreover, because of their conservative attitudes towards sex, attacks like these also produced profound feelings of shame in the victims and were generally not discussed outside the families where they had occurred. Eventually, a man was apprehended one night sneaking into a house and, upon questioning, gave details of several accomplices from the village who had also been involved in these nighttime rapes. The men were reported to the Bolivian authorities. People began to discuss the events more broadly. It turned out that some of the girls had hazy memories of waking up during the night and having the impression of a man lying on top of them before falling back into a deep sleep. A trial ensued and, after a great deal of persuasion, some of the victims testified in court. Eight men were sentenced and sent to jail. Nevertheless, some 10 years later the echoes of these events continue to reverberate in the Bolivian Mennonite community.

But how exactly had the perpetrators of these crimes managed to sexually assault a large number of women without them really being conscious of what was going on and, moreover, why were the other members of the household also oblivious to these events? The answer is that prior to entering the victims’ homes, the criminals used a spray to aerosolize a drug into each house through open windows. The drug employed had the effect of narcotizing their victims, producing a state resembling deep anesthesia together with amnesia the following morning. As things turned out, the drug was one that was already used by some people in the local area to anesthetize cattle prior to surgical procedures. The drug had been adapted for use as a spray. What was the drug? According to several reports it was “isolated from a local plant”. According to one report it was “belladonna”.

Does this make any sense? Quite possibly, although the precise details are unclear. The drug referred to as belladonna is commonly known as atropine. Atropine and a related drug known as scopolamine can produce a huge number effects and can be employed for many different purposes. At higher doses both drugs are deadly poisonous. Indeed, the traditional source of atropine, the plant Atropa belladonna, is commonly known as the “Deadly Nightshade”. Atropine and scopolamine can actually be obtained from a large number of plants which grow in many parts of the world. These plants are all members of the Solanaceae or Nightshade family (which also includes tobacco, bell peppers, eggplants, tomatoes and potatoes) including the genera Atropa, Brugmansia, Datura, Duboisia, Hyoscyamus and Scopolia, as well as Mandragora, the Mandrake plant which was discussed in a previous blog post. Many species from these genera contain the same active drugs. It isn’t clear that in Bolivia it would actually be Atropa belladonna that was the plant source in this case but more likely a member of the Datura or Brugmansia genus, all of which grow abundantly in parts of Bolivia. Nevertheless, whatever the source, the drug purified from the plant and its effects would be more or less the same. Indeed, as we shall discuss, these drugs have been used for many purposes for thousands of years. One famous historical figure, the Jesuit monk Bernardino de Sahagun, who became part of the Spanish administration of Mexico in the 17th century and wrote widely about the habits of the indigenous population, called attention to Datura in the following words: “It is administered in potions in order to cause harm to those who are objects of hatred. Those who eat it have visions of fearful things. Magicians or those who wish to harm someone administer it in food or drink. This herb is medicinal and its seed is used as a remedy for gout, ground up and applied to the part affected.”

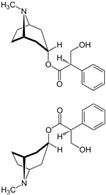

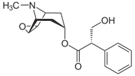

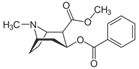

The chemical substances responsible for the effects of these plants are known as tropane alkaloids. Atropine in a mixture of the two stereoisomers of the molecule hyoscyamine, and scopolamine is the molecule hyoscine. As you can see, they only differ in structure by one oxygen atom and their pharmacological properties are very similar. However, it is worth pointing out that not all tropane alkaloids derived from South American plants have similar properties. Indeed, the drug cocaine, which is derived from the plants of the Erythroxylaceae family, has a similar chemical structure but completely different pharmacological properties, being a powerful psychostimulant.

It is interesting to note that the use of drugs like scopolamine to produce a profound state of anesthesia, amnesia and compliance to the wishes of another individual is not unique to the Mennonite community in Bolivia. According to other reports, the same drug is all the rage in different parts of South America being used for similar purposes. For example, a recent somewhat over-the-top report from the online news service Vice illustrates the situation in Bogota, Columbia, where it seems scopolamine is widely used by criminal gangs (see video below). In these cases, the gangs slip some of the drug into the drink of an unwitting individual and then when the victim becomes intoxicated they can be made to empty their ATM or give away all their worldly goods. If the victim is a woman they may also be raped. When subsequently asked what happened to them, the victim seems to have completely forgotten. It seems that people in Bogota are widely aware of the effects of scopolamine and, according to the report on Vice, it is generally regarded as the “most dangerous substance known to man”.

Like most drugs that produce profound psychotropic effects, the effects of atropine and scopolamine are produced by interacting with neurotransmitter systems in the brain—neurotransmitters being the chemical messengers that carry information from one nerve cell to another or from a nerve cell to a target tissue. In this case, the neurotransmitter involved is acetylcholine, the very first neurotransmitter ever to be discovered. Acetylcholine produces its effects by acting on two different types of receptors known as nicotinic and muscarinic receptors. Both types of receptors are widely distributed in the peripheral nervous system and also in the brain. In this instance, it is the muscarinic receptors that are the targets of interest. Both atropine and scopolamine are potent blockers of muscarinic receptors and as both drugs can enter the brain, they have effects on both the central and peripheral nervous systems. In the peripheral nervous system, the muscarinic effects of acetylcholine mostly involve actions on smooth muscle contraction and glandular secretions. At appropriate doses, atropine and scopolamine (or nowadays, their semisynthetic derivatives) are extremely widely used in medicine. The drugs can produce effects such as the relaxation of muscles, effects that can be extremely useful. For example, they are used therapeutically in treating asthma where muscarinic blockers produce relaxation of the lungs. Their antispasmodic actions are useful in the treatment of bladder spasms, irritable bowel disease, peptic ulcer, colic, cystitis and pancreatitis. The drugs are also widely used for producing dilation of the pupils prior to an eye examination. In ancient times women would use atropine to dilate their pupils, which was thought to make them look more attractive, and this is the reason why atropine got its original common name of belladonna (beautiful lady). It seems that Cleopatra was a fan. At more elevated doses, however, effects on the central nervous system begin to show up. Indeed, even today student doctors all learn that the salient features of atropine use are “Hot as a hare: increased body temperature, Blind as a bat: mydriasis (dilated pupils), Dry as a bone: dry mouth, dry eyes, decreased sweat, Red as a beet: flushed face and Mad as a hatter: delirium”.

The deliriant effects of atropine and scopolamine have been well known for thousands of years, leading to their use in witchcraft and magic. It has been widely reported that when under the influence of these drugs one has the impression that one is flying, and that they were key ingredients in witches’ flying ointments. The ability of the drugs to put a patient into a stuporous state have also been widely described throughout history. It is said that the sponge offered to Jesus on the cross contained these drugs. Also, ancient physicians would employ a “soporific” sponge in which hot water and extracts of plants containing drugs like scopolamine would be held under the noses of patients who were undergoing surgery.

It is therefore not surprising that their use for this purpose was “rediscovered” in the early part of the 20th century. In 1903 Dr. Carl J. Gauss, a doctor in Freiburg Germany, devised a procedure which he named “Dammerschlaff” which is usually translated as “Twilight Sleep”. This involved giving a pregnant women a mixture of morphine and scopolamine prior to delivery. Under these circumstances the woman would be more or less unconscious while giving birth, would feel little discomfort and would remember almost nothing about the entire experience. The idea became something of a craze. Women in the USA, for example, demanded the treatment and a society named the National Twilight Sleep Association was founded in order to put pressure on physicians to provide it. Generally speaking, physicians were obliging and the procedure became widely used in the first two decades of the 20th century. It turned out that although women didn’t remember their experiences during twilight sleep, quite a lot was going on. The deliriant effects of scopolamine were frequently apparent with women flailing around and vocalizing while delivering. They were placed in special ‘birthing cots’ with their wrists and ankles strapped to the sides so that they wouldn’t harm themselves while they tossed and turned, sometimes in their own vomit, until their baby had been safely delivered with forceps. Another issue with the twilight sleep procedure was that the drugs would frequently cross the placenta and depress the behavior of the newborn. This resulted in the practice that the doctor would give babies a brief slap on the bottom as soon as they were delivered to make sure they were breathing. The unfortunate side effects of twilight sleep were the subject of a celebrated article in the Ladies Home Journal in May 1958, in which many patients and nurses spoke out about their experiences. As a result, the use of the procedure gradually declined and the pendulum began to swing in the opposite direction as natural birth procedures came into vogue.

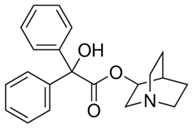

Of course, the ability of drugs like atropine and scopolamine to produce a state of delirium and amnesia was something that came to the attention of the CIA in the 1950s. Drugs like these, or others including psychedelics such as LSD that could produce altered states of consciousness, were intensively investigated as possible weapons in the Cold War. These aims were generally pursued as part of the CIA’s MK-ULTRA program which was concerned with potential chemical brainwashing and subversion a la Manchurian Candidate. Of course, the CIA didn’t stop with scopolamine and atropine. Much better weapons were soon available. After the war, the Hoffman La Roche company in Basel had a program to make better spasmolytic agents based on the tropane alkaloid structure. One of the molecules they came up with in 1951 was 3-quinuclidinyl benzilate (QNB), a semisynthetic tropane alkaloid which, as you can see, does look a lot like atropine.

The drug company tested it as a treatment for ulcers. It turned out that however good it was for ulcers, it was certainly better at making people delirious. What was more, the drug was fantastically potent. You only need microgram amounts to precipitate hallucinations. Soon the drug was in the hands of the CIA where it was renamed BZ or “Buzz”. From the mechanistic point of view, Buzz proved to be a really potent antagonist of muscarinic receptors, much more potent than atropine or scopolamine. Moreover, Buzz gets into the brain very easily. Once it is in there it hangs around for a long time producing extended effects. Dr. James Ketchum, one of the people who did secret work on the drug for the army and CIA at the Edgewood Arsenal in the early 1960s, wrote about Buzz,

“Not only did it work, but its effects lasted a long time. At just above half a milligram volunteers consistently became stupefied. After 4-6 hours, they were usually ‘out like a light’. By 12 hours they were moving around again, but were totally disoriented and unable to do much of anything. Forty eight hours later, they were usually approaching normal on their performance tasks. A day or two after that they had completely recovered….it took almost three years and an estimated 100,000 hours of professional effort by physicians, nurses, technicians and volunteers to learn all the things we wanted to know about Buzz”.

And just what were those things? What could the CIA want to know about what was one of the most powerful deliriants ever invented? It was the 1950s and anti-communist paranoia was very much in the air. The CIA played around with a lot of sci-fi ideas as to how Buzz aerosols might incapacitate entire populations or groups of soldiers on the battlefield. As far as we know, this never actually came to anything. However, the subject has recently resurfaced with reports that terror groups like ISIS have now got their hands on materials like Buzz and are actively employing them on the battlefield. And it wasn’t only the CIA who recognized that the delirium induced by drugs like Buzz might be used for mind-control purposes. It is quite clear that drugs of this type have been used by several cult-like groups in efforts to control the minds of their adepts. One notable example was their use by Charles Manson, perpetrator of the Tate/La Bianca murders, to maintain psychological domination over the members of his “family”.

So, although the CIA never used tropane alkaloids to incapacitate the armies of their enemies, it seems as though some members of the Mennonite community of Manitoba came up with the similar idea for equally nefarious purposes. As with so many ancient drugs, each generation rediscovers them and uses them for its own purposes.