“Beware of the Powers that never die

though men may go their way,

The Power of the Drug, for good or ill,

shall it ever pass away?”

– Agatha Christie (from In a Dispensary)

One of the many unfortunate consequences of the current COVID-19 pandemic has been the closure (temporarily, one hopes) of many theaters, cinemas, music clubs and other locales where people normally like to congregate for the purposes of entertainment. Although there is no real substitute for these things many individuals and institutions have found ways of presenting events online. The recorded live performances of plays from the National Theater in London, for example, has provided a really wonderful opportunity for watching great plays featuring some of the best actors in the world—all of this completely without charge. In addition, it is clear that, deprived of their normal opportunities for going out, people have been watching many more programs on the TV. And, these days, there are many excellent shows to choose from. Although I have watched my fair share of TV programs during the current lockdown, my fallback entertainment has been to watch police/detective dramas. There have been many excellent mystery series from England and America , but also from other countries, including dramas set in Iraq (Baghdad Central), Tokyo (Giri/Haji) and Iceland (Trapped). Of course, there are always the old favorites to fall back on and I admit to having sat through most episodes of Midsomer Murders at least twice and, of course, there is always Agatha Christie. Agatha Christie invented two of the most beloved investigators in the detective pantheon: the Belgian sleuth Hercule Poirot and the spinster Miss (Jane) Marple. Indeed, if we run the numbers, Agatha Christie’s stories turn out to be the most popular of all time, and not just in the detective genre. Her prolific literary contributions include 66 detective novels, over 100 short stories and 17 plays, including the world’s longest-running play, The Mousetrap. She is the best-selling novelist of all time, according to the Guinness Book of World Records, with around two billion copies of her books having been sold worldwide since her first detective novel, The Mysterious Affair At Styles, which introduced the legendary Hercule Poirot, was published in 1920. She is the author of the world’s best-selling mystery novel, And Then There Were None. Her books have been translated into at least 103 languages (can I even name 103 languages?) and have generated a staggering 7,236 translations, vastly outnumbering the second most translated author, Jules Verne with 4,751. FYI ,Verne is followed by William Shakespeare (4,296 translations), Enid Blyton (3,924), Barbara Cartland (3,652), Danielle Steel (3,628) and ,believe it or not, Vladimir Lenin (3,593—is there a “laugh a minute Lenin” that I didn’t know about?). From my point of view however, Agatha Christie is of particular interest because pharmacology features regularly in her plots. Indeed, drugs and poisons play important roles in about two thirds of her stories. This isn’t that surprising once you know that Agatha Christie was a trained pharmacist and so had a considerable knowledge of drugs and how they work.

She was born Agatha Mary Clarissa Miller on 15 September, 1890 into a wealthy family in Torquay, Devon in the UK. During the first World War, she volunteered at the Red Cross hospital in Torquay as an assistant nurse. When a dispensary (pharmacy) was installed in the hospital, she was asked to serve in it and eventually took an examination to become licensed as an assistant pharmacist. After this two-year tour of duty as a pharmacist during World War I and a second tour of duty at University College Hospital in London during World War II, she had become an expert on the effects of drugs in general. In over 60 of her novels and short stories, she described more than ninety drugs including many dangerous ones that are usually found in the locked poison cabinet of any pharmacy including arsenic, insulin, morphine, potassium cyanide and strychnine. This seems like a good time to review some of the uses of poisons in her stories, and we can start with a couple of excellent examples!

Agatha Christie began using poisons as part of her plots in her very first published mystery, The Mysterious Affair at Styles. The poison involved in this case was strychnine, which is obtained from Strychnos nux-vomica, the strychnine tree. The Strychnos genus is actually a large one comprising some 200 species which can be separated geographically—Central and South America (73 species), Africa (75 species), and Asia, Australia and Polynesia ( 44 species). These different plants may appear as erect or climbing shrubs, lianas or trees. Because of their toxicity, many of these species have been used since ancient times as arrow poisons by indigenous peoples for hunting purposes. Strychnos nux-vomica, which originates in India and southeast Asia, is often the source of the drug strychnine, and its effects would have been well known to Agatha Christie.

From the chemical point of view, strychnine is an alkaloid like morphine, nicotine, coniine and many other active substances derived from natural sources. Several other alkaloids, such as brucine, also occur in Strychnos nux-vomica, but strychnine is usually the most abundant. The drug was first isolated in 1818 during the early phase of organic chemistry when many new natural products, mostly alkaloids, were being identified for the first time. Its activity as a poison in crude extracts had been known for many years prior to that, and it was used in Europe as a rodenticide and for killing different types of wild animals. It was also clear that it was extremely toxic to humans and indeed, strychnine had been used as an agent in numerous celebrated murders. One of the best known cases of that era is that of Thomas Neil Cream, who poisoned a series of London prostitutes with strychnine in the 1890s. Before he was hanged, Cream also tried to take credit for the crimes of Jack the Ripper, but this is unlikely to be true. A widely publicized earlier case was that of William Palmer, who was executed for the strychnine murder of a friend but suspected of also killing four of his children, who all of died of convulsions prior to their first birthdays.

In Agatha Christie’s story, it is the wealthy Mrs. Inglethorp who is murdered. Screams emanating from her bedroom wake everybody up one morning, and upon entering her room she is observed to be suffering from extreme convulsions which “lifted her from the bed, until she appeared to rest upon her head and her heels, with her body arched in a most extraordinary manner.” She dies a horrible death and this leads to an investigation that is eventually solved by Poirot (of course). Poirot determines that she was murdered by strychnine, although the manner in which this happened was very unusual. Strychnine is horribly poisonous but, like many other poisons, it is sometimes used in very low doses as a stimulant medicine. Of course, this is playing with fire, because the “therapeutic window”—that is, the margin between the dose at which it can be safely used as a tonic and the dose at which it is poisonous—is very narrow. In other words, it is very easy to take too much. It turns out that Mrs. Inglethorp was taking low doses of strychnine as a tonic. She was also taking “bromide” as a sleep aid. The devilishly clever murderer had taken some of her bromide and put it into the bottle of her strychnine tonic. This caused the strychnine to precipitate out as a salt and fall to the bottom of the bottle. So, when Mrs. Inglethorp took the last dose of tonic from her bottle containing the precipitate, she was actually taking a very highly concentrated and obviously fatal dose of strychnine! This story tells us, among other things, that you really never know when at least some basic training in pharmacology and chemistry might come in useful.

In her story, Agatha Christie’s description of the symptoms of strychnine poisoning were extremely accurate, as would be expected from somebody with her training. Pure strychnine is a colorless, white powder with a famously bitter taste. Only about 1 mg/kg body weight is necessary to kill a human. The initial symptoms of strychnine poisoning are excitability and heightened awareness followed by vomiting and muscle contractions. Developing convulsions last from 30 seconds to 2 minutes. Extreme muscle overextension and spasticity occurs and victims take the form of what is known as “opisthotonic” posturing with back arched, extremities extended and jaw clenched. Patients may demonstrate risus sardonicus, muscle contractions of the face causing the fixed, stiff appearance of a sardonic smile. Uncontrolled muscle contractions can lead to tachycardia, hyperthermia and airway compromise from stiffness at the jaw and neck. Next the muscles begin to tear themselves apart and fluids leak out of them into the bloodstream, leading to conditions such as rhabdomyolysis, hyperkalemia, lactic acidosis, metabolic acidosis, kidney failure, and seizures. As death approaches, the convulsions follow one another with increased rapidity, severity and duration. Death results from asphyxia due to prolonged paralysis of the respiratory muscles, especially the diaphragm. A really horribly violent way to die!

How does strychnine produce its remarkable effects? The most important inhibitory neurotransmitter in the spinal cord is known as glycine, and strychnine is a powerful blocker of glycine receptors. The removal of glycine’s inhibitory effects causes uncontrolled stimulation of postsynaptic motor nerves leading to involuntary, diffuse muscle contractions. Because it does not affect the higher motor neuron centers of the brain, victims typically present with severe muscle contractions that appear as if they are having “awake seizures” and so are conscious of their ongoing destruction. The glycine receptors expressed by motor neurons in the spinal cord are constructed in a very similar manner to the GABA-A receptors that mediate nerve inhibition in many parts of the brain. They are channels that open when glycine binds to them and allow the movement of negatively charged chloride ions across the cell membrane, which hyperpolarizes neurons and inhibits their ability to fire action potentials. Strychnine is really a pretty good choice for poisoning somebody if you want them to die a really horrible death.

A second interesting story I watched during the pandemic was Agatha Christie’s 4.50 from Paddington. This is the story of the eccentric Crackenthorpe family, and several murders take place along the way. The first murder which gets the plot going occurs on a train leaving Paddington station. Mrs. McGillicuddy is traveling on an adjacent train and when she looks over across the tracks, she sees what appears to be a man strangling a woman. Nobody believes her story because no body has been found. Fortunately, Mrs. McGillicuddy is a friend of the redoubtable Miss Jane Marple, sleuth extraordinaire, who does believe her friend’s story and sets out to solve the crime. Events lead her to the local country house home of the Crackenthorpes during a yearly birthday gathering to celebrate their forebear, who originally accumulated the family fortune but left it to his descendants through the workings of a complicated will, setting them against one another. Two other members of the family then suddenly die, the result of poisoning. Eventually it is uncovered that the poisons employed were arsenic and aconitine. Arsenic, of course, is almost a byword for poison. But it is aconitine that is the really poisonous agent in this instance.

The genus Aconitum contains over 250 species of perennial flowering plants that commonly grow wild, but some species are also frequently cultivated for their attractive and showy inflorescence. Nearly all species of the plant are extremely poisonous, and extracts are known as “The Queen of Poisons.”The flowers have a very particular shape, appearing rather like tiny helmets that might have been worn by an ancient Greek soldiers or possibly the hoods of monks or friars, and the plants are often known as “monkshood “or “devil’s helmet.” Because extracts of the plant were used to kill wolves in ancient times, they are also often called “wolfsbane.” There are many stories as to the origins of these deadly plants. The author Gustav Meyrink, famous for his surrealist description of the Golem, told the tale of Cardinal Napellus. He was the founder of an ascetic sect. When Cardinal Napellus himself died, a blue monkshood plant, completely covered in blossoms, grew up from his grave to the height of a man in a single moonlit night. When the grave was opened, the corpse had vanished. The cardinal was said to have changed himself into the plant and all others since are supposed to have been derived from it. Subsequently, behind the walls of his monastery, lay a garden which in the summer was full of these deadly plants. The monks watered them with their own blood, which gushed from wounds inflicted by their acts of self-flagellation. Each monk, when he became a brother of the community, had to plant and care for one of the flowers which was given the name, Aconitum napellus.

Other stories about Aconitum have come down to us from antiquity.The Greek word akónitos is derived from ak = pointed and kônos = cone, an akon being a dart or javelin, possibly a reference to the plant’s use as arrow poison. The Greeks thought that the plant grew from the spittle of Cerberus, the three-headed hound of Hades. Ovid tells a story in Metamorphoses VII, in which sorceress Medea attempted to poison Theseus with Aconitum. Ovid also tells us that Athena sprinkled Arachne with juice of Aconitum, upon which she was transformed into a spider. Aconitum was also named hecateis, after the goddess Hecate. Hecate was an ancient Greek goddess of witchcraft, and so had a profound knowledge of herbs and poisonous plants. Aconitum is also thought to have been used by witches as one of the ingredients in their hallucinogenic flying ointments. Most interesting from my point of view was that Pliny’s name for the plant was “plant arsenic” and that it was the “most prompt of all poisons.”

However, just as in the case of strychnine, very low concentrations of Aconitum have been widely used as stimulants and medicines. The use of Aconitum tinctures for such purposes is particularly common in Asia. In traditional Ayurvedic Indian medicine, for example, Aconitum extracts, albeit in tiny amounts, have been used for a whole host of indications including as an anti-pyretic, anti-rheumatic, cardiac stimulant, abortifacient, aphrodisiac, and anthelmintic as well as for the treatment of cough, asthma, snakebite, vomiting, and diarrhea. However, as little as “eight drops” of a tincture have been reported to cause severe poisoning. It therefore not surprising that there are also numerous tales of people who have died from taking these medicines because, whatever merits tiny doses of Aconitum tincture might have, like strychnine, it would be extremely easy to take even slightly too much, resulting in a deadly effect. Indeed, it would obviously be a simple matter to use an extract of Aconitum for some dark purpose. And indeed, Aconitum has been used in several famous murders in modern times and, presumably, many others stretching back to antiquity. One fairly recent example was that of Dr. George Henry Lamson who killed his brother-in-law with a poisoned cake in 1881 in an attempt to increase his share of the family inheritance. He was under the impression that Aconitum was undetectable by forensic testing, but he was wrong and was tried, found guilty and hanged. There is also a story of a woman who confessed to having murdered her abusive husband by homogenizing three Aconitum plants in his favorite red wine and giving it to him for his dinner.

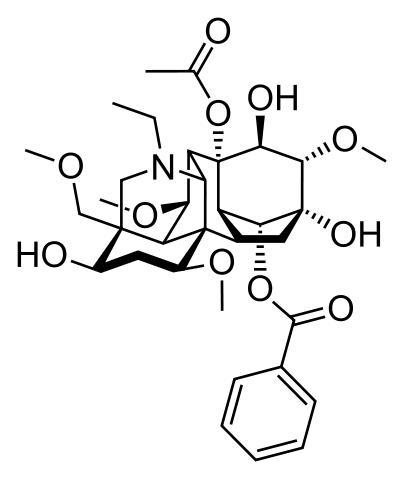

Aconitine alkaloids are the active principles responsible for the toxic effects of the “Queen of Poisons.” Aconitine itself is the most common component, but there are also related molecules found to varying extents in different Aconitum species, including mesaconitine, hypaconitine yunaconitine and jeaconitine, all of which are also toxic to greater or lesser extents. Their cellular targets are the voltage-dependent Na+ conducting channels found in nerve cells and cardiac muscle. Aconitine and related toxins prevent Na+ channels from closing at the appropriate point in time after a cell has fired an action potential, leading to abnormal excitation of nerves and muscles. Effects like this on the heart, for example, will soon lead to the occurrence of fatal arrhythmias.

Most recently, however, there was a celebrated incident in England where many people originally from South Asia now live and, as I have mentioned, people from South Asia are often acquainted with Aconitum owing to its use in Ayurvedic medicine. The story, one which Agatha Christie would surely have relished, concerns the murder of one Lakhvinder “Lucky” Cheema and the poisoning of his girlfriend, Gurjeet Choongh, who lived in the Feltham district of West London. About a month prior to the murders, Mr. Cheema had spent a week in hospital with a set of mysterious symptoms including headache, vomiting and numbness of the hands, but had recovered and was discharged. However, these events were only a prelude to what was to come later. On the day in question, Mr. Cheema and Miss Choongh, who had been discussing plans for their wedding, sat down to a dinner of curry which had been left over from a previous meal and which they had warmed up. A little later Mr. Cheema reported that his face had become numb and he could no longer feel it when he touched it. A short time after that Miss Choongh started feeling similar symptoms and Mr. Cheema called for an ambulance. When they reached hospital, Miss Choongh became comatose and suffered a large number of cardiac arrhythmias before she was stabilized and ventilated for two days before finally recovering. On the other hand, two hours after being admitted to hospital, Mr. Cheema died. Prior to his demise, the main symptoms he presented consisted of intense and continuous vomiting, visual disturbances, muscle weakness, dilated pupils, cardiac arrhythmias and metabolic acidosis. All in all, it was a very nasty way to die. The fact that two apparently healthy young people from the same household had simultaneously become extremely ill obviously suggested that the cause was the same—perhaps some kind of infection or food poisoning? Foul play was certainly also suspected, and investigations centered on the contents of the meal they had both shared. For several months, nothing turned up but eventually there was an answer. The curry in question had contained Aconitum alkaloids, the chemical substances that are responsible for the effects of Aconitum. As a result, Ms. Lakhvir Singh, Mr. Cheema’s ex-girlfriend, was indicted for the murder of Mr. Cheema and causing grievous bodily harm to Ms. Choongh. As it turned out, Ms. Singh, a woman trapped in an unhappy arranged marriage, had been carrying on an affair with Mr. Cheema for some 16 years. She had even become pregnant twice but in each case Mr. Cheema had insisted she have an abortion. It is said that Ms. Singh visited Mr. Cheema’s house every day to clean and cook his food, behaving in all respects like a devoted wife, in spite of the fact that she was actually married. But Mr. Cheema then met Ms. Choong, a much younger woman, and had tried to end his relationship with Ms. Singh. Driven mad by jealousy, she had then planned and carried out the murder by sneaking into Mr. Cheema’s house and dosing the curry with extracts of Aconitum, which were subsequently found to be stored in her home.

The use of strychnine and aconitine are only two examples of the many uses Agatha Christie made of her knowledge of drugs. Reading her stories usually provides an accurate description of the symptoms that accompany different types of poisons, and her work was sometimes reviewed by pharmacology journals in addition to newspapers and magazines, something that apparently gave her an enormous amount of pleasure. As can be seen from these two examples, Agatha Christie had an excellent working knowledge of poisons and their effects. This leaves us another 60 or so examples of the murderous use of poisons to return to in the future.