Like many people, I have had ample opportunity to read a large number of books during the pandemic, both fiction and non-fiction. I was given a copy of Maggie O ‘Farrell’s book “Hamnet: A Novel of the Plague” and the title certainly caught my attention. Along with The Decameron and Camus’ The Plague, both of which I reread, the title of the novel clearly states its relevance to our current situation. It turned out to be a very interesting book. The story is about a playwright who lives in Stratford-upon-Avon at the end of the 16th century, but who is never named (I wonder who that might be?) and concerns the fate of his son Hamnet. Apparently, the names Hamnet and Hamlet were considered equivalent at the time. One of the things the book achieves very effectively is a vivid description of what it was like to live in an English town during the Elizabethan period. Something that I found particularly interesting was that Hamnet’s mother (whose name is Agnes in the book) is a healer (as opposed to a doctor) and is constantly using different types of medicinal herbs which she grows and prepares herself. Agnes makes a living by dispensing her remedies to the citizens of Stratford when they are ill and come to consult her. It is very interesting to see what kinds of things she used and how these were part of the practice of medicine at the time.

The action of the book takes place around the year 1583. At that time, one of the worst fates that might befall you was being treated by a medical professional, what we would call a doctor today. Such a thing would usually ensure your hasty demise because very little was actually known about medicine from our current perspective. Most of the things doctors did to you made no scientific sense whatsoever and were liable to make your illness worse. The major reason for this was that the general theory of disease in Tudor times was completely incorrect. Medicine in the 16th century was based on the work of the great Greek/Roman doctor Aelius Galen who lived in the third century CE and was certainly, along with Aristotle and Hippocrates, one of the most influential figures in the history of medicine. Galen was responsible for the development of experimental medicine in antiquity and he discovered many interesting facts about the nervous and cardiovascular systems. Unfortunately, he interpreted all of his results according to the humoral theory of disease, something that he appropriated from Aristotle. This theory postulated that the effective functioning of the human body depended on the actions of four humors—blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile—which were obtained from eating food and breathing air. These humors also had other properties. Blood was hot and wet, phlegm was cold and wet, yellow bile was hot and dry and black bile was cold and dry. Good health depended on these humors being “in balance.” Galen developed the concept of plethora, or an overabundance of a particular humor as the cause of a disease. As manifestations of disease, the presence of blood and phlegm were obvious. Yellow bile was found in the gall bladder and was observed when the patient became jaundiced. The effects of black bile were apparent in conditions where the skin became black. The recommended treatment for any disease was to redress the balance between the humors through purging, starving, vomiting or bloodletting. Bloodletting was a very common treatment during the Tudor period. It is said that the barber’s red and white pole commemorates this fact—the red stripe representing bloodletting, and the white stripe the tourniquet to stem the bleeding. Cupping was also used to remove excess bodily humors. A small glass was heated and applied to the skin. The vacuum created by the glass cooling was supposed to suck harmful substances out of the body. Purging was used for problems of the stomach and alimentary canal. Emetics or laxatives were administered for cleansing the body of an overabundant humor. Based on ideas like these, if somebody had a fever, for example, the explanation was that the patient was suffering from an overabundance of hot blood and so the treatment was bloodletting using leeches or a similar method. Galen wrote a great deal and his work was widely respected. Following the fall of Rome in 476 CE, his ideas spread from Western Europe to the great Arab empires that stretched from Baghdad to Spain and became an entrenched medical doctrine throughout Europe and the near East for at least the next 1200 years. Very little changed over that vast period of time.

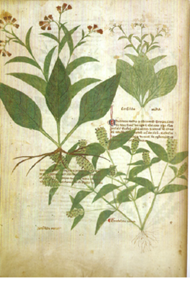

In addition to the treatments administered by doctors, there was also a tradition of folk medicine— natural cures derived from plants—and, whereas the treatments performed by doctors seldom worked, many valuable naturally occurring drugs had been discovered over thousands of years of informal human experimentation. These included things like opium (morphine) for pain, willow bark (salicylic acid) for pains and fevers, and foxglove (digoxin) for dropsy (edema—a primary symptom of heart failure). The effects of these plant extracts were interpreted through the concepts of humoral medicine as being the result of a redistribution of humors and, even though this was not the reason for their effects, they certainly could be very helpful in practice. In general, medicines like these were administered by healers such as Hamnet’s mother Agnes. Indeed, as illustrated in the book, healers and doctors were often in competition with one another for the same patient population. When Hamnet’s sister Judith comes down with bubonic plague, she is visited by a “plague doctor” in his traditional regalia.

In order to cure Judith of the plague, the doctor gives Agnes a package to tie to her daughter’s abdomen. The package contains a dried toad. As the doctor explains to Agnes, “you must trust that I know more about these matters than you do. A dried toad, applied to the abdomen for several days, has proven to have great efficacy in cases such as these.” Agnes declines his offer. It is hard to know why ineffective remedies such as these persisted over so many centuries but, of course, there were always patients who improved spontaneously, and doctors could point to them as being genuine successes.

As it turns out, around the time that the novel takes place, the science of therapeutics was undergoing a great change. This was due to the influence of alchemy, whose general aims of turning base metals into gold or discovering the philosopher’s stone—a source of immortality—were based on the science of chemistry. The high priest of this approach at the time was one Philippus Theophrastus Aureolus Bombastus von Hohenheim, usually known as Paracelsus. Paracelsus was brought up in a southern region of Austria known as Carinthia, which was a center of the burgeoning mining industry where new chemical elements were being discovered. Paracelsus was an iconoclast and completely disagreed with Galen and the way he practiced medicine. For example, he replaced Galen’s set of four humors with three humors of his own: salt (representing stability), sulfur (representing combustibility), and mercury (representing liquidity). More importantly, the way Paracelsus went about treating disease was completely different. Rather than attempting to rebalance the humoral state of the body, he suggested using particular chemical agents, often highly purified through the use of distillation and related chemical techniques, for treating specific diseases which, he hypothesized, might be the result of problems with individual organs rather than due to humoral imbalance of the entire body. Paracelsus recognized that the drugs he used, which were typically metals or extracts prepared from plants and other natural sources, would have different effects according to the dose employed, saying “All things are poison and nothing is without poison; only the dose makes a thing not a poison,” which is, of course, a classic tenet of the science of pharmacology. Something like mercury could be extremely toxic at one dose but might have selective benefits at a lower dose. The introduction of the use of chemistry to prepare drugs, the idea that dosage was important and the concept that drugs should target particular organs, all presaged a much more modern approach to therapy, one which was completely different from the Galenist theories employed by the Plague Doctor. Agnes’ methods were much more in line with the coming chemical approach to medicine, even though neither she, nor Paracelsus, had any real idea as to the mechanisms underlying a drug’s beneficial effects. Paracelsus’ insights had probably not reached Stratford in 1583, but they would soon. In the meantime, Agnes’ ideas concerning the beneficial effects of her preparations were based on Galenic interpretations.

For example, at the start of the book Agnes’ daughter becomes seriously ill. As soon as Agnes becomes aware of the physical symptoms of her daughter’s disease, she rushes downstairs to prepare a remedy. She begins with rue and cinnamon which are “good for drawing out the heat,” to which she adds bindweed root and thyme. Then she adds rhubarb “to purge the stomach and drive out the pestilence.” Her thinking relies on drawing out and purging excess humors. Nevertheless, she is attempting to achieve these aims by using plants that do, in truth, contain active chemical ingredients. No dried toads or magic incantations. Unfortunately, Agnes is really up against it because her daughter’s infection with the bacterium Yersinia pestis (bubonic plague) is not easily treated except with an antibiotic.

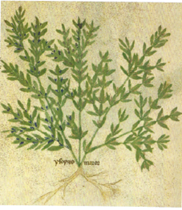

We all know about cinnamon, thyme and rhubarb. But how about rue and bindweed root? Rue has a particular resonance in this story because it also features in Shakespeare’s Hamlet when the mad Ophelia declares, “There’s rue for you; and here’s some for me; we may call it herb of grace o’ Sundays. You must wear your rue with a difference.” Rue refers to Ruta graveolens,which was often used as an ornamental plant owing to the color of its blue/green leaves. Rue has a bitter taste and, in former times, was used a symbol of regret and repentance. It was often used to signify these sentiments in phrases such as “rue the day.” Ophelia also refers to the plant as a “herb of grace on Sundays.” This was because when entering a church on a Sunday, the wearer dipped the rue in Holy Water—which always stood within the portals—and blessed himself with it, hoping to obtain God’s grace or mercy. Rue not only symbolized bitterness but was a major cause of abortion in its day, which is why it was also associated with adultery. Ophelia keeps a rue flower for herself but also gives one to Gertrude and says that she “must wear her rue with a difference.” Clearly Gertrude’s rue symbolizes something different than Ophelia’s. One might conclude that Ophelia was filled with bitterness due to the awful things Hamlet said to her as well as her father’s death, and that Gertrude’s rue represented adultery.

The chemical constituents of rue have been widely studied. Of course, like any plant it contains thousands of natural products that have interesting chemical structures and which might have effects on humans. When Agnes gives somebody an extract of rue as a remedy, this will contain a huge number of different chemicals mixed together, and trying to elucidate which one is responsible for any observed effect would be a very difficult problem, even today using the most up-to-date analytical techniques. Rue has a particularly high alkaloid content, which presumably accounts for its bitter taste—alkaloids like strychnine, morphine and nicotine are always bitter. It is also the source of the chemical rutin, which was named after the plant and has been investigated for its therapeutic potential. A recent review considered some 50 possible uses for this compound! However, at this point in time, none of these applications are well established according to the strictest modern criteria. Nevertheless, Agnes would have had a great deal of experience using rue, and this is a key consideration, because she certainly would be aware of its effectiveness in the context of her practice.

Note the blue and white Morning Glories

The word bindweed in 16th century England probably refers to the plant Convolvulus arvensis, often known as the “field bindweed,” or possibly Castylegia sepium, the “hedge bindweed.” Another common name for these plants and others in the same family is “Morning Glory.” These plants are characterized by their trumpet-shaped flowers which are normally white or pink but can be other colors such as blue or violet. Morning Glories are usually considered invasive weeds but are sometimes cultivated for show. One particularly interesting thing to note about these plants is that some varieties contain the compound ergine or lysergic acid amide (LSA). This is very close in structure to lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), which is an extremely powerful hallucinogenic drug. Indeed, chewing Morning Glory seeds was often used by indigenous peoples in South America in pre-Columbian times as a way of inducing a transcendental state of mind. However, LSA is very weakly hallucinogenic compared to LSD and, moreover, the seeds usually contain the highest concentration of the drug. So, whether the bindweed root extract used by Agnes had any hallucinogenic effect is unclear. The plants are also reported to contain tropane alkaloids which are often biologically active—both atropine and cocaine are tropane derivatives. Consumption of crude bindweed root extracts are reported to produce vomiting and have laxative effects, which would be consistent with a desire to use them for purging. The powdered roots of rhubarb, which Agnes also added to the remedy, were also widely used at the time as a laxative purgative. One can therefore see that the combination of plants used by Agnes to treat her daughter would contain a wide variety of bioactive molecules and would likely produce a rather strong purging reaction by eliciting vomiting and diarrhea, as well as possibly producing some mild psychotropic effects. Regrettably, none of these things would really be of much use when trying to treat bubonic plague.

In another example, Agnes attempts to self-medicate when suffering from cramps prior to the delivery of her twins, Judith and Hamnet. She uses a combination of honey, valerian and chickweed which she reports don’t help very much. Honey was frequently added to cover up the unpleasantly bitter taste of many of plant extracts. Valerian root (V. officinalis) has been used since antiquity for the treatment of anxiety, tension and insomnia, and there is some contemporary evidence that it might actually do just that. Extracts of these plants known as “valerian” have a long history of medicinal use dating back to the era of the Greek physicians Hippocrates (circa 460-377 BCE), Dioscorides (1st century CE) and Galen (circa 130-200 CE), who all prescribed it for insomnia among other complaints, and it was still being used for this purpose in Tudor times. It is possible that the hypnotic actions of valerian may be produced in a similar fashion to those associated with benzodiazepine drugs like Valium. The targets for these drugs are the receptors for the neurotransmitter GABA, which has an inhibitory effect on nerve cells in the brain. Benzodiazepines enhance the effects of GABA on its receptors and so inhibit nerve activity. A recent study demonstrated that some of the chemicals that are found in Valerian, such as isovaleric acid (3-methyl-butanoic acid), can inhibit the enzyme GABA-transaminase which normally metabolizes GABA in the brain. Such an action would cause synaptic levels of GABA to rise and might therefore produce a hypnotic effect.

Chickweed (Stellaria media) is a common plant with small white star-shaped flowers employed as ground cover in many parts of the world. It is widely used as a salad ingredient and in folk medicine. Again, as with many herbal remedies, a large number of uses for the plant have been suggested over the centuries, including treatment of gastrointestinal disorders, asthma, diarrhea, measles and jaundice as well as renal, digestive, reproductive and respiratory tract inflammation. Moreover, as with valerian, anxiolytic activity has been reported when extracts of the plant are given to mice. Overall, the use of a mixture of valerian and chickweed might be expected to have some kind of calming effect on Agnes, although it is unlikely to abolish severe cramps associated with delivering a baby ( it turns out she is having twins!).

Portrait of a girl holding rosehips.

Rockingham castle, Leicestershire

Not all the plants mentioned in Hamnet are for treating illness. In another episode, Agnes’ daughters ask her about making their yearly expedition to collect rose hips. The family traditionally made syrup out of rose hips for treating coughs and colds. This particular year, however, following the death of her son, Agnes finds the bright red color of the rose hips difficult to appreciate as they clash with her somber mood and, moreover, the whole business of picking them, preparing them and cooking them seems like something that is beyond her strength to deal with at the time. The harvesting and utilization of rose hips must normally have been very pleasant for the family. Rose hips are the accessory fruits that grow on rose plants after the flowers have fallen off. They are the pods that contain the seeds for propagating new roses. But, if you are growing the plants for their flowers, they are traditionally cut off, because roses produce better flowers that way. Seed pods like these form on many flowering plants and sometimes have interesting properties. Consider the seed pods that form on poppies after their flowers have fallen off, which are the source of the drug opium. Agnes and her daughter were going to search the hedgerows for rose hips that grew on wild roses. Rose hips are very popular, even today, for making syrups, jams and medicines. Just like all the other plants mentioned, rose hips contain many interesting chemicals that might produce useful medicinal effects but these are still under investigation using rigorous modern scientific approaches. One thing that is quite clear, however, is that rose hips are particularly rich in vitamin C, something that is certainly good for treating colds. So, rose hips are a “win-win” crop—delicious and good for you! I remember as a young boy at school going through the ritual of receiving a spoonful of rose hip syrup every day from the matron—something I certainly looked forward to.

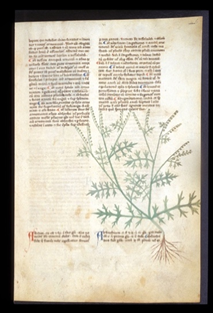

There are numerous other medicinal herbs mentioned in Hamnet. Here are a few others with interesting old fashioned names that might be new to you.

Comfrey: (Symphytum officianale). Comfrey has been used for centuries as a traditional medicinal plant for the treatment of painful muscle and joint complaints. Indeed, the name Symphytum comes from the Greek symphis, meaning growing together of bones, and phyton, a plant. Comfrey is a perennial shrub that is native to Europe and some parts of Asia. It has a thick, hairy stem, and grows two to five feet tall. Its flowers are dull purple, blue or whitish, and densely arranged in clusters. Comfrey roots and leaves contain allantoin, a substance that helps new skin cells grow. Comfrey ointments have been used to heal bruises as well as pulled muscles and ligaments, fractures, sprains, strains, and osteoarthritis. The therapeutic properties of comfrey also include its anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects. Although it is not known exactly which chemical components of comfrey are responsible for these effects, it does contain rosmarinic acid which has been shown to possess anti-inflammatory activity in several test systems.

Hyssop: (Hyssopus officinalis). Hyssop is a small perennial plant which grows about two feet tall with slim woody quadrangular stems. The narrow elliptical leaves bear spikes of little flowers—usually violet-blue, pink, red, or white. Hyssop comes from the mint family and has been grown since ancient times for its aromatic properties. The plant has a sweet scent and a warm bitter taste and has long been used as flavoring for foods and liquors, which may be the reason why Agnes was growing it in her garden. It has also been used as a medicinal herb as it contains high concentrations of phenol, which give it antiseptic properties. Interestingly, it also contains high concentrations of thujone, which is an antagonist of GABA receptors. As mentioned above, activation of GABA receptors has a calming effect and so substances like thujone ,which do the opposite, have strong excitant effects. Indeed, taking too much purified hyssop extract (essential oil) can actually produce seizures.

Feverfew: (Tanacetum parthenium). Feverfew looks a lot like a daisy and is in the same family of plants (Asteraceae). The name feverfew comes from the Latin febrifugia, meaning a reducer of fevers—again illustrating its ancient use in folk medicine. Indeed, it was documented in the first century CE as an anti-inflammatory drug by the Greek herbalist physician Dioscorides. More recently, it has been evaluated for migraine prophylaxis and it has been shown to produce beneficial effects. Although the exact mechanism of feverfew’s action is unknown, it is believed that a sesquiterpene lactone called parthenolide is the active ingredient and works by inhibition of several potential inflammatory mediators of migraine including cyclooxygenase-2, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin-1 (IL-1).

Wormwort: This one is a bit of a mystery. Plants of the genus Artemesia are sometimes called wormwood or sometimes mugwort or sagewort—but “wormwort” appears to be a combination of the two names and so it is difficult to know exactly what is meant here. Most likely it is Artemisia absinthium (common wormwood), a plant with silver feathery foliage and yellow flowers that appear in early summer. Plants of this genus are famously bitter and some of this flavor is imparted to absinthe, the liquor made from A. absinthium, which may be the reason why Agnes was growing it. Shakespeare referred to wormwood in Romeo and Juliet: Act 1, Scene 3, Juliet’s childhood nurse declaring, “For I had then laid wormwood to my dug,” meaning that the nurse had weaned Juliet, then aged three, by using the bitter taste of wormwood applied to her nipple. A. absinthium also contains thujone and so might have potent excitatory effects if used inappropriately. It is interesting to note that plants from the Artemisia family contain many potent substances, some of which have been extremely useful. The prime example of this was the discovery of the widely used anti-malarial drug artemisinin from the Sweet Wormwood plant A. annua by the Chinese scientist Tu Youyou, something for which she was awarded the Nobel Prize in medicine, the first Chinese woman to receive the award. This discovery shows us that the herbs used by Agnes are still likely to reveal new treasures even after all these years. Many of the herbs Agnes used really do produce interesting effects and, in many instances, we still don’t quite know why.